Echocho and the Okura State Dream: When a Senator Becomes the Voice of His People

By John Akubo

As the National Assembly reopens the long-shut doors of constitutional reform and state creation, one movement has surged with renewed momentum — the demand for the creation of Okura State from the present Kogi State. While the agitation dates back over four decades, what distinguishes this phase is not just the compelling constitutional argument or historical justifications, but the emergence of a lawmaker who has taken ownership of the cause with unflinching clarity and strategic commitment: Senator Jibrin Isah (popularly known as Echocho), representing Kogi East Senatorial District.

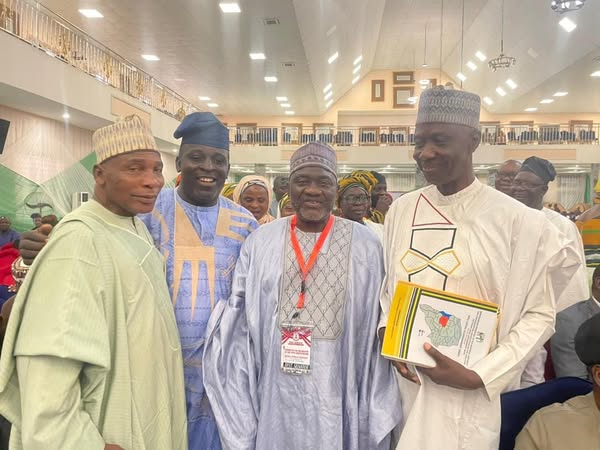

In a country where state creation is often treated as political tokenism, Echocho’s campaign has placed the Okura State movement on solid constitutional and economic grounds. His recent appearance at the Senate Zonal Public Hearing on Constitutional Review in Jos, backed by strategic lobbying and cross-party engagement, signals a serious intent to take the issue beyond rhetoric.

The agitation for Okura State is far from a new phenomenon. Its origin can be traced back to the Second Republic, where it featured prominently among state requests approved for referendum in 1983. But the military’s interruption of democratic governance scuttled what could have been a defining moment. Decades later, other states in similar categories have been created. Okura was left behind.

The proposed state covers nine local government areas — Ankpa, Dekina, Idah, Ofu, Omala, Ibaji, Olamaboro, Igalamela/Odolu, and Bassa — which together form the original Igala Native Authority. With a population of over three million and a landmass of 14,000 square kilometers, the region meets and even surpasses the constitutional thresholds set out in Section 8 of the 1999 Constitution (as amended.

Yet, proponents argue that despite being the largest and most populous senatorial district in Kogi State, Kogi East has remained structurally shortchanged — with fewer local governments, state constituencies, and federal allocations than its counterparts.

What is changing the dynamics of this struggle is the emergence of Senator Echocho as a legislative anchor for the movement. At the Zonal Public Hearing, the Senator did more than accompany his constituents — he spoke, lobbied, negotiated, and affirmed his resolve to make Okura State a legislative reality.

So far, Echocho has reportedly secured the endorsement of 55 Senators, a remarkable feat considering the ethno-regional politics that often plague state creation. He has promised to ramp up these numbers in the weeks ahead, recognizing that the road to constitutional alteration is paved with consensus.

In his own words:

“When I return to the Senate, I will secure more signatures. This is not about just my people; it’s about the economic and political justice Nigeria owes this region.”

His argument is not emotional. It is developmental. He makes the case that Okura, already a contributor to Nigeria’s mineral wealth — including oil, coal, and agricultural exports like cashew — has the potential to become a self-sustaining state, contributing meaningfully to national GDP.

While leading the agitation at the national level, Echocho is also transforming the landscape of Kogi East through infrastructural and human capital development. From a proposed ICT hub in Ankpa to roads and hospitals across Itobe, Ajaka, and Ugwolawo, his projects serve both as dividends of democracy and a preamble to what Okura State could look like if birthed.

His upcoming “mega empowerment programme” — designed to transcend partisan lines and include traditional and religious leaders — is a clear attempt to forge unity within the district, which has sometimes been polarized by internal politics.

Critically, Echocho’s ability to coordinate with the three members of the House of Representatives from Kogi East ensures that the agitation benefits from a full legislative front — a rare feat in Nigeria’s fragmented representation culture.

If Okura State is created, it will be the first state in Nigeria since 1996. Beyond the symbolism, it will signal a renewed responsiveness of the National Assembly to legitimate grassroots agitations. It will also set a precedent for other long-standing movements such as Adada, Aba, and Katagum states.

Echocho’s leadership in this agitation demonstrates what is possible when lawmakers prioritize the structural and economic empowerment of their constituents over the distractions of everyday politicking. His approach blends historical memory with present-day advocacy, while aligning with constitutional due process.

In a country burdened by structural imbalances and regional discontent, the call for Okura State offers a legitimate opportunity for redress. Senator Jibrin Isah has stepped into a historic role — not just as a politician, but as a statesman who has chosen to carry the burden of a people’s longing for justice.

Whether the dream materializes in this constitutional cycle or the next, what is certain is that the agitation is no longer an orphan. It has found a champion in Echocho — and in the chambers of the Nigerian Senate, that might be the gamechanger.

The ball is now in the court of the National Assembly.

Will they act? Or will they delay a destiny that is already knocking loudly at Nigeria’s constitutional gate?