Bringing The People Back In: Ibas And The Inclusive Governance Agenda

By Berewari Gogo

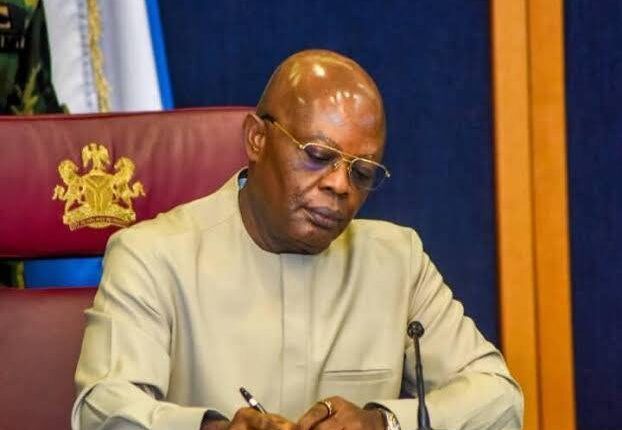

In times of political upheaval, one of the first casualties is often the people’s trust in government. For too long in Rivers State, the political drama between entrenched interests has played out like a tragicomedy, sidelining citizens and reducing governance to a game of thrones. But since the appointment of Vice Admiral Ibok-Ete Ibas (retd.) as the sole administrator of the state, a noticeable shift has occurred—one that places the people, rather than the politicians, at the centre of statecraft.

The idea that governance should be for the people is not novel. What is novel, especially in the context of Rivers State, is a political administrator actively creating platforms and policies that reflect this ethos. From his first week in office, Ibas has reoriented the machinery of government towards what can only be described as inclusive governance. Unlike predecessors whose governance style was dominated by elite bargaining and partisan patronage, Ibas has chosen to engage the ordinary citizen.

One of his earliest moves was the establishment of a Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Council made up of representatives from youth organisations, women groups, the physically challenged, traditional institutions, labour unions, faith communities, and civil society. The Council serves as a sounding board for government decisions and a channel for grassroots feedback. Not only has it met regularly, but its inputs have been reflected in several policy adjustments—from how palliatives are distributed to the selection of projects under the emergency infrastructure renewal plan.

Beyond institutional arrangements, Ibas has brought governance to the streets. Town hall meetings have been held in all three senatorial districts, sometimes in local dialects, ensuring that no demographic feels alienated. These aren’t ceremonial visits; they’re working sessions where issues ranging from flood control to market sanitation are addressed with remarkable responsiveness. This open-door approach has begun to close the psychological gap between the government and the governed.

Nowhere is this inclusive spirit more evident than in the area of youth engagement. For a state whose youthful population has often been weaponised by political godfathers for thuggery and disruption, Ibas’s administration is charting a new course. The Youth Service Corps Reintegration Programme, launched in April, targets unemployed former NYSC members from Rivers with short-term paid internships across various ministries and local government offices. The initiative not only boosts employment but also promotes civic responsibility and skills acquisition. Over 600 graduates have already benefitted.

The administration has also prioritised women’s voices in governance. A landmark executive directive issued in May mandates that all government committees must comprise at least 35% women representation. In a state where tokenism often replaced genuine inclusion, this policy has already begun to shift the culture. At the last Economic Empowerment Fund disbursement, more than half the recipients were women entrepreneurs in agriculture, fashion, and renewable energy.

Inclusiveness is also being felt in rural and riverine communities. Previously neglected areas now have a say in the state’s development priorities. Through the Rural Development Participatory Budgeting Model (RDPBM), local leaders submit development needs directly to the Ministry of Planning. From potable water boreholes in Abua to solar-powered streetlights in Andoni, the outcomes speak for themselves.

Critics have dismissed some of these initiatives as cosmetic, arguing that true inclusion requires electoral legitimacy. While that may be true in a textbook democracy, the reality on the ground demands more nuanced assessment. In a transitional emergency regime, what matters is not just who holds power but how that power is exercised. Ibas has made it clear that his mandate is to prepare Rivers State for a return to democratic governance by rebuilding the bridge between the people and the state.

More importantly, this model of inclusive governance is creating a template for future administrations. By institutionalising citizen engagement and feedback mechanisms, Ibas is not just solving today’s problems; he’s building tomorrow’s political culture. One where community voices are not seasonal tools for campaigns but permanent fixtures in policymaking.

The true test of any administration lies in how it treats the most invisible members of society. Under Ibas, the differently-abled have found new visibility. The State Council for Disability Affairs, which had been dormant for years, was reactivated in June with funding support and a seat at the weekly Executive Council meetings. Accessibility ramps are now mandatory in all new public buildings, and disability-inclusive disaster response drills have been conducted in areas prone to flooding.

This is not to romanticise the Ibas administration. Challenges remain, including scepticism from entrenched political players and institutional inertia in some ministries. But there is little doubt that an alternative form of governance is being piloted—one grounded in access, voice, and shared responsibility.

As Rivers State moves towards the end of emergency rule, one legacy seems certain: the reintroduction of citizens into the heart of governance. That, perhaps, is Ibas’s most important reform—one that will outlive his tenure and serve as a benchmark for inclusive governance across Nigeria.

Berewari Gogo writes from Bori