A Crisis ECOWAS Cannot Ignore: Why The Gambia Must Step In Now

By K. S. Lawal

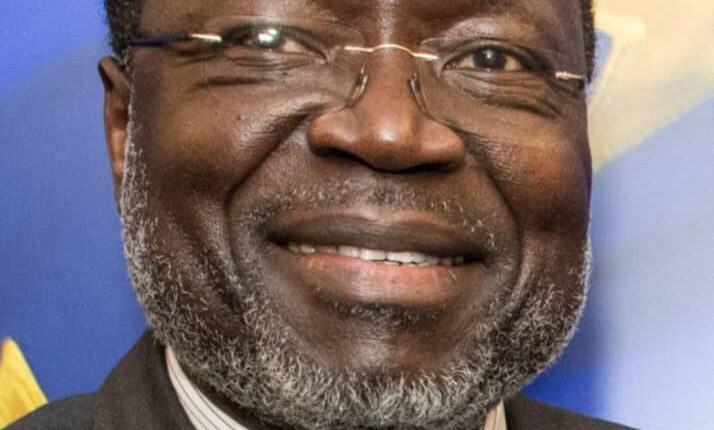

ECOWAS stands today at a crossroads, not because of a foreign threat or the spread of coups that have destabilised parts of West Africa, but because internal decisions taken at the top of its administrative structure now threaten the organisation’s integrity. At a time when the region needs stability, principled leadership and restoration of public confidence, the conduct of the President of the ECOWAS Commission, Dr Omar Alieu Touray, has placed an avoidable burden on ECOWAS and, by extension, on his home country, The Gambia. What should have been a routine administrative matter has escalated into a governance crisis that now demands diplomatic intervention at the highest level. The Gambia must now act, not only to save ECOWAS but also to protect its own long earned reputation.

The crisis stems from a memo issued on 30 October 2025 in which Dr Touray allegedly revoked all delegated authority from a Nigerian Commissioner, Professor Nazifi Abdullahi Darma, without involving the ECOWAS Council of Ministers. The organisation’s governing instruments are clear about the process for disciplining or sanctioning Commissioners. Only the Council of Ministers, as the appointing authority, can do so. The matter is now before the ECOWAS Court of Justice after Professor Darma approached the court to challenge the action as a breach of the organisation’s treaty provisions. Whatever the eventual judicial outcome, the allegations alone have exposed troubling governance patterns that require immediate correction, and The Gambia must not ignore the responsibility placed on its shoulders as the home country of the Commission President.

The ECOWAS Treaty and its supplementary protocols are explicit. Commissioners are not subordinates of the President of the Commission. They are political appointees representing sovereign nations, and only the ECOWAS Council of Ministers has the power to discipline, suspend or remove them. Any action to the contrary is not a matter of discretion, but a violation of the institutional architecture of the organisation. When the head of the Commission bypasses this structure, the entire organisation is thrown into disarray. Rules cease to hold meaning, legitimacy becomes contested and the door opens for arbitrary decision making.

In ordinary times, the Commission would have the internal strength and cohesion to manage such disputes quietly. But these are not ordinary times for ECOWAS. Three member states have already walked away from the regional body. A fourth is still struggling with its transition. Insecurity continues to spread through the Sahel. Public trust in regional institutions has plummeted. A misstep at the top of the Commission, especially one involving a senior official from Nigeria, weakens the institution further, embarrassing the region and emboldening critics who argue that ECOWAS has lost its moral compass.

The Gambian dimension adds a layer of complexity that cannot be ignored. Dr Touray is Gambian. So is the Director of the Cabinet of the Commission, Mr Abdou Kolley. The two most powerful administrative positions in ECOWAS are now held by nationals of the same country. On its own, this is neither unlawful nor unprecedented. But when allegations arise that Commissioner level functions were being channelled to an appointee who is also Gambian, concern becomes unavoidable. Institutions run on balance. Leadership must be beyond suspicion. Even when no wrongdoing is proven, perception alone can cause corrosive damage.

The perception now spreading across the region is that one country may be exercising disproportionate influence within the Commission. This is unfair to The Gambia. It is unfair to its people. It is unfair to the democratic tradition they fought to rebuild. And it is unfair to the spirit of ECOWAS, which thrives on equality and representation. Unless The Gambia acts swiftly, it will find itself wrongly associated with the conduct of one individual rather than the values that define its nationhood.

To understand the weight of the present moment, one must recall the history of Nigeria’s relationship with The Gambia and the subregion. Nigeria has been the anchor of West Africa for four decades, bearing the financial and military burden that keeps ECOWAS alive. Over 85 percent of the organisation’s operational costs come from Nigeria. Nigerian troops fought and died in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea Bissau under ECOWAS mandates. Nigeria has consistently provided political cover and diplomatic leadership during periods when the subregion was on the brink of collapse.

For The Gambia specifically, Nigeria played an extraordinary role. When former President Yahya Jammeh attempted to cling to power after losing the 2016 election, Nigeria stood at the forefront of the diplomatic push that secured a peaceful transition. Nigeria supplied judges to Gambian courts. Nigeria supported the reform of Gambian security structures. Nigerian professionals and civil servants have, for years, contributed to strengthening the country’s institutions.

This long history matters. It is a relationship built on trust and sacrifice. Any perception that a Nigerian Commissioner has been targeted through an irregular or unilateral process threatens this foundation. Diplomacy is sensitive to symbolic gestures. What appears to be a simple administrative overreach can quickly become a diplomatic injury, particularly when it involves the nation without which ECOWAS would simply collapse.

The upcoming ECOWAS statutory meetings in Abuja this December will bring all these tensions into sharp focus. Ministers, diplomats and Heads of State will gather to chart the way forward for a region struggling with fragmentation. Instead of entering these meetings united, ECOWAS risks being engulfed by internal controversy. Delegations will not only discuss security and development but also whisper about cracks within the Commission. The Gambia, to its detriment, will find itself at the centre of that conversation unless it acts honourably and proactively.

The solution is neither complicated nor hostile. It is diplomatic and responsible. President Adama Barrow must recall Dr Touray. A recall does not imply guilt. It does not taint the integrity of The Gambia. Instead, it protects the country’s reputation, restores balance within the Commission and allows a cooling off period during which ECOWAS can fix the governance anomalies that have brought it to this point. Recalling the Commission President is a stabilising measure, not a punitive one. It signals that The Gambia remains committed to fairness, equity and the stability of the regional body that once came to its aid.

More importantly, it sends a strong message that no individual, no matter how highly placed, is more important than the unity and dignity of a subregion already weighed down by crises. ECOWAS cannot afford internal destabilisation at a time when extremist threats are expanding, democratic structures are weakening and citizens are losing faith in regional cooperation. Allowing an administrative dispute to evolve into a diplomatic rift between Nigeria and The Gambia would be reckless and unfortunate. A firm and respectful intervention is the only path forward.

The Gambia must act now, not with fear but with clarity. The honour of the country, the integrity of ECOWAS and the stability of the subregion depend on it. In moments like this, leadership is not measured by silence but by the courage to safeguard the collective good. This is The Gambia’s moment to act. The region awaits its decision.

K. S. Lawal is a Regional Affairs Commentator.